The following is a review of selected literature about jumping in digital games.

|

| "Moon Patrol requires players to jump their buggy over craters and other hazards." (Begy, 2010) |

Jason Begy. “The History and Significance of Jumping in Games.” GAME//PLAY//SOCIETY: Contributions to Contemporary Computer Game Studies. Proceedings of the 4th annual Vienna Games Conference. Kopaed: Munich, Germany, 2010.

https://web.archive.org/web/20140207165134/http://www.jasonbegy.info:80/Begy_Jumping.pdf

Begy uses Ian Bogost's Unit Operations (2006) text as his guide and analyzes linguistic metaphors ("GOOD IS UP") for the appeal of both jumping and climbing in digital games. He also shows a relation to tabletop games where climbing up levels (snakes and ladders) and jumping over obstacles (chess knight) and "leaping captures" (checkers/draughts, alquerque, hala-tafl) are primary game mechanics.

Begy asserts that Mario's static jump in Donkey Kong, while only a defensive means of avoiding an obstacle, should be considered as an "act of dominance: once leapt over they effectively become harmless" (pg. 15). This may be true of the barrels that continue rolling down the platforms of the first stage, but fireballs may change direction and chase Mario.

The paper includes short analyses of Pitfall, Moon Patrol, Manic Miner, and Super Mario Bros. Like Swink in Game Feel, Begy ignores the arcade game Mario Bros. (1983) and confusingly refers to SMB as "Mario Bros."

Begy concludes that humans have a positive orientation metaphor with height (GOOD IS UP) that may be an embodied metaphor, something more than cultural in origin. This metaphor gives meaning to the action of jumping and may be key to the mechanic's popularity in digital games.

|

| "Mario Jump" (Butler, 2014) |

Tom Butler. "The Rise of the Jump." Polygon. 2014.

Butler's history starts with the Universal arcade game Space Panic (1980), probably the first "platformer" game, though the game has no jumping. There are quotes from researchers, such as Begy, and a guide to finding examples of different aspects of jumping in games (double-jump, jump attack, triple jump, partner-assisted jump, etc.).

|

| "Players control a rolling ball. Their task is to collect three stars." (Dahl and Kraus, 2015) |

Gustav Dahl and Martin Kraus. "Measuring How Game Feel is Influenced by the Player Avatar's Acceleration and Deceleration: Using a 2D Platformer to Describe Players' Perception of Controls in Videogames." AcademicMindTrek '15: Proceedings of the 19th International Academic Mindtrek Conference. September 2015. Pages 41–46.

https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2818187.2818275

Dahl and Kraus were directly influenced by Swink's Game Feel (hence, the title of their paper) when they designed their experiment in changing parameters of a platformer's "game feel" and measuring player experiences. As important as this notion is to the aesthetic pleasure of experiencing a digital game, we still don't have a robust vocabulary for critiquing or analyzing game feel.

The results were somewhat inconclusive. The vocabulary the participants used to describe game feel was varied ("heavy," "slow," "realistic," etc. (pg. 15)), as I would have expected. Some users were sensitive to small changes in game feel while others didn't notice and difference. The experimenters note that "game feel" is still an odd term for users, one they compare to "mouthfeel." Users did note an inability to find the right words to describe their experience, another sign that we are lacking in language to define these aesthetics.

|

| "Subtle implementation details found while measuring the jumps." (Fasterholdt, Pichlmair, & Holmgard, 2016) |

This thesis is a deep dive analysis of subtle details of jumps in different games. The analysis is focuses on Super Mario Bros. 3, Super Meat Boy, and Limbo, but also looks at some other games.

Fasterholdt designed his own tools for creating precise, simulated controls in a game for measurement and analysis. He used Unity to build his own replications of the games he analyzed, much like I've been doing with my own Traversing Virtual Dimensions project.

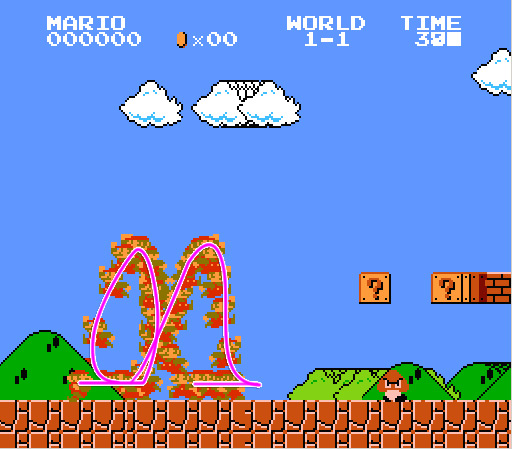

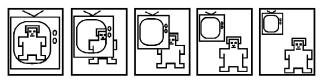

The study shows how differences in gravity, terminal velocity, friction, take off velocity, "jump release," and other parameters change how a game character feels while jumping. He also found helpful jump allowances that enable a player to jump even when the character is not on the ground. Some games use a "jump cache" (image a, above): when a player presses the jump button while in mid-air just before landing, the game will "cache" that jump command and jump as soon as the character lands. Similarly "edge jump" (what I call "coyote time") lets the player still jump after they've just stepped off the edge of a ledge.

|

| "Demonstration of some neat tricks to make platforming games feel better." (Strachan, 2020) |

Strachan created a platformer game template in Game Maker that exemplifies some of the "subtle implementation details" that Fasterholdt identifies in his thesis. This sample template is playable on his blog page and the project is freely available on his Git Hub repository.

In addition, Strachan analyzes the jump arcs of a number of 2-D platformers, complete with time in the air, the number of frames of animation, and other information about jump parameters.