My research work is focused on the development of an "art history" of digital games, a diachronic view of game history as the creation and development of aesthetic styles, rather than simply a history of technological advancements. My work is often confused with the establishment of game genres (platformer, FPS, RTS, etc.), which isn't exactly correct. However, I realize that certain spatial paradigms are commonly shared by certain game genres and I thought it would be a good idea to look at how the concept of "genre" came to be applied to video games.

One early attempt at categorizing games into specific types comes straight from Atari, a dominant force in arcade video games and home console games throughout the 1970s and early 1980s.

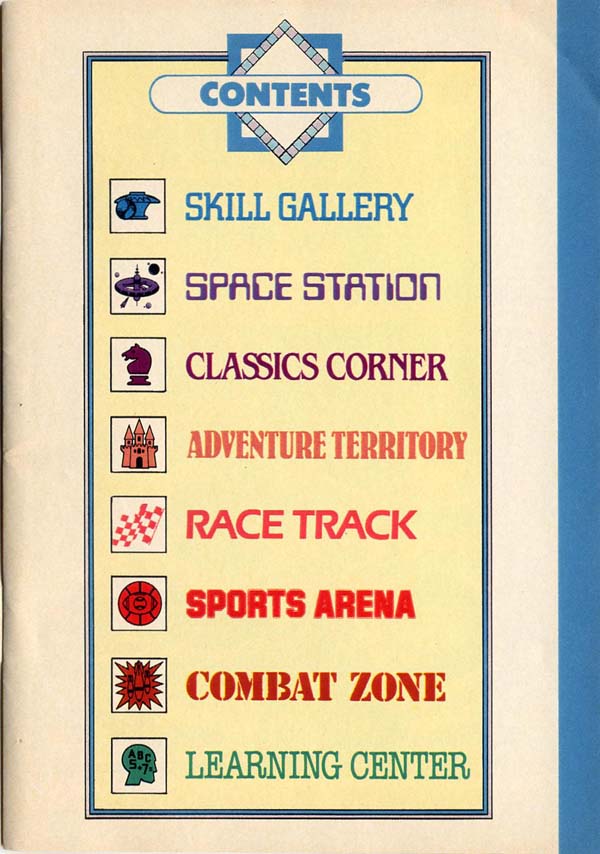

Atari Catalog CO16725-Rev. D

|

| Contents page from Atari Catalog CO16725-Rev. D (1981) |

Atari produced several different full-color catalogs to showcase the "Video Game Program cartridges" available for their programmable Atari VCS (later renamed the Atari 2600) home console. Previous Atari consoles were dedicated to play only one game or a small selection of games that were stored in fixed ROM chips. The VCS was their first console where the game programs could be swapped out, allowing for a potentially unlimited number of games to be played.

Atari's first "Innovative Leisure" catalog features the eight different game cartridges that were available near the system's launch in 1977. By early 1981 when catalog CO16725-Rev. D was published, the VCS catalog had grown to 45 different cartridge titles (not including titles that had been dropped from production in the intervening years). For the first time, Atari needed to organize the expanding catalog into chapters, breaking up the titles into a number of game genres.

These genre categories remained consistent, almost unchanged through 1983's catalog CO21776-Rev. A. By 1983, Atari had also released the Atari 5200 system and the VCS was newly dubbed the 2600. 1984's catalog CO25618-Rev. A showed off the then-new (and ill-fated) Atari 7800 system, in addition to the 2600 and 5200, and the genre categories were given revised names. [The 1984 names are noted in brackets, below.]

- Skill Gallery [Skill & Action] (Breakout, Pac-Man, Circus Atari, Video Pinball)

- Space Station [Space] (Space Invaders, Missile Command, Asteroids)

- Classics Corner (casino and board games)

- Adventure Territory (Haunted House, Adventure, Superman)

- Race Track [More Adventures] (car driving games)

- Sports Arena [Sports and Atari RealSports] (sports games, including Video Olympics (a collection of Pong variations))

- Combat Zone [More Adventures] (Air-Sea Battle, Combat, Outlaw, Warlords)

- Learning Center [Kid's Library] (BASIC Programming, Codebreaker (includes Nim), A Game of Concentration, Hangman)

The implied purpose behind this system is one of informing consumers about a product line and as a marketing tool to show the wide variety of games available from Atari (important in the light of competitors like Activision cropping up to produce VCS cartridges that competed with Atari's own line). So, it may be less useful as a tool for research than a system intended to be a formal taxonomy of digital games would be. However, there are still some formal aspects that can be teased out of this organization.

Some of these game genres are similar to film genres (Space Station/science fiction, Combat Zone/war movie). These are categories focused on the aspects of representation rather than qualities of interaction (Thomas H. Apperley, "Genre and Game Studies: Toward a Critical Approach to Video Game Genres," Simulation & Gaming, Vol. 37 No. 1, March 2006 pg. 7) that describe the milieu (pg. 11) of a specific game. Presumably, from a marketing standpoint, fans of related forms of entertainment in other media (film, television, or literature) may be inclined to play digital games in a related genre (sports fans may tend to choose games from Sports Arena, for example).

Some categorization options are puzzling. Space Station game Missile Command is about defending cities against attack in a nuclear war, which thematically seems more appropriate for Combat Zone. Combat Zone game Warlords can mechanically be described as 4-player Breakout, but it is not included in Breakout's Skill Gallery category. Hangman and A Game of Concentration (the flipped-card matching game variously called pairs or memory) are "classic" game examples, seemingly fitting of Classics Corner, but are included in Learning Center. I suspect that Atari wanted to give the impression that the VCS had plenty of educational titles and padded out their Learning Center category with games that are playable by younger children.

Interestingly, all categories are named after a type of place (gallery, station, corner, territory, track, arena, zone, or center). This implies a location where games of a certain genre may be found and experienced. Flipping through an Atari catalog is almost an early, transmedial, analogue version of navigation through digital media. 10+ years later, this same sort of locational language would often be used to organize locations for different types of digital files on web sites (and even on BBS services before that). Together, they form the World of Atari.

The Adventure Territory games all happen to share a common mechanical quality. Adventure, Haunted House and Superman are games where the player's on-screen avatar explores a large, multi-screen environment. As the avatar reaches one edge of the screen, it reappears on the opposite edge with the screen framing the next section of the gamespace.

Atari's genre system can be used as a contrast to the more analytical types of systems that I analyze in the following Game Genres blog posts.

/Update%2003/85-shield.gif)