Media/Culture Journal founder Nicholas Caldwell came to game studies from film studies and soon realized that our field lacks a vocabulary for discussing the formal qualities of digital games. "Where was the grammar of the game?," he asked. Like other game studies scholars, he expressed frustration at not having a common language to discuss core aspects of a game's aesthetics.

In his "Theoretical Frameworks..." paper, linked above, he documented his attempts to introduce a framework for a specific type of game: turn-based computer strategy games. He chose this type due to his familiarity with them and the relative homogeneity in representational and temporal approaches in them. The exemplar game of his analysis is Civilization II (1996).

|

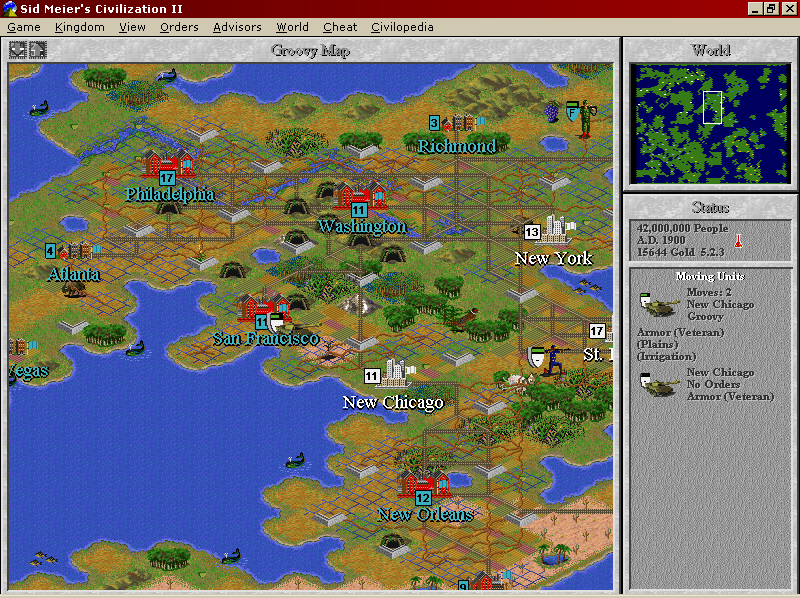

| Civilization II (MicroProse, 1996, Windows 3.1) screen shot |

Caldwell adopts a semiotic approach to analyzing a game's visuals, using Charles Peirce's typology of signs, as processed by Stephen Poole in Trigger Happy: The Inner Life of Video Games (2000). Caldwell attempts to describe the Civ II screen, like the one above, using his terminology for the formal characteristics of the symbolic visual display. However, his chosen terms immediately come in conflict with my own terminology and other standards for game graphics terminology, such as the University of Montreal's Game FAVR system ("Game FAVR: A Framework for the Analysis of Visual Representation in Video Games," Arsenault, Côté, & Larochelle, 2015), which I have written about before.

The screen space is dominated by the main map window, which displays (with a term borrowed from architectural drawing) an isometric view of the game space, which is a forced perspective rendering of the elements of the map, giving the illusion of depth to the image.

The main map window uses a dimetric projection using a 2:1 grid line ratio ("isometric" in gamer vernacular, this is the same method used since Zaxxon and Q*bert, and at least one artist calls it "pixel isometric." But formally, this is a dimetric view. Newer games like Monument Valley are truly isometric, but it is a difficult projection for older games like Civ II). This game space uses projection, not perspective, and there is little or no illusion of depth in the image. The illusion of depth would require perspectival clues like convergence, vanishing points, and size difference as objects get further from the game camera. Other minor techniques can give an illusion of depth, such as parallax motion, aerial diffusion, tonal separation, textural (detail) difference, but none of these are in Civ II (I adopt the Visual Story teachings of Bruce Block, who I studied under, to digital game visuals). The only depth cue is the fact that some game elements overlap other game elements, implying they are "closer" to the viewer.

Such a projection does not imply a single, favored, subjective viewpoint as there is no perspectival organization of space from which a virtual camera may be assumed to observe the game environment. All game objects are presented equally, all being about the same size on the screen.

Unit icons (hereafter referred to as ‘sprites’ — a term in game design used to refer to any animated element on a computer screen)...

The term sprite has been used in a number of ways in game development, but it typically refers to a two-dimensional game object, which typically uses a bitmapped graphic, that can move across the game environment. Sprites may or may not be animated. This is in contrast with environmental objects that do not move and often take the form of tiles, though tiles also may or may not be animated.

Caldwell continues to analyze Civ II and its foundations in the philosophy of Cartesian Perspectivalism. This has little to do with the visual presentation of game space and everything to do with the player as a postmodern, rational, disembodied subject whose very gaze organizes and controls the world within its focus. He adopts Foucault's metaphor of the panopticon as the game's mechanics are based on supervision and surveillance, as supported by the technology of the interface.

Caldwell never gets the chance to analyze the temporal organization of games like Civ II, something he regrets at the end of the paper. So far, I haven't been able to find a follow-up article written by him that continues this analysis.