Chris Crawford's "Taxonomy of Computer Games"

|

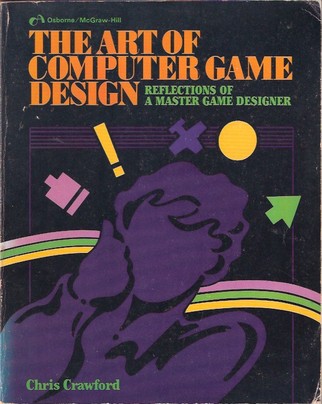

| The Art of Computer Game Design (Crawford, 1984) |

Chris Crawford wrote what is now considered the first "game studies" text with his pioneering book, The Art of Computer Game Design (1984). Chapter two of the book describes his "Taxonomy of Computer Games," his attempt "illuminate the common factors that link families of games, while revealing differences between families and between members of families" (pg. 19).

Crawford explains that we game designers can "learn a great deal about game design by establishing a taxonomy of computer games." A well-constructed taxonomy would "suggest previously unexplored areas of game design," and, "reveal underlying principles of game design" (pg. 19). Crawford does not consider his definitions to be definitive, he admits that "a number of games do not fit into [his] taxonomy" (pg. 29), but it serves as an early effort to study and understand this then-new aesthetic form.

Crawford states that a taxonomy "is only one way of organizing a large number of related elements" and that "[constructing] several alternate taxonomies may be a useful way to examine the common traits of computer games" (pg. 29). This is exactly why I am undertaking this examination of early game genre systems and will incorporate all the information from these blog posts into my personal game research database.

Crawford broadly groups most games into "Skill and Action" games ("emphasizing perceptual and motor skills" (pg. 19)) and "Strategy" games ("emphasizing cognitive effort" (pg. 19)).

Skill and Action

- Combat Games ("direct, violent confrontation" (pg. 20))

- Maze Games (including Maze Craze, Dodge 'Em (driving game, but in a maze), and Pac-Man)

- Sports Games

- Paddle Games (covers the "PONG-based games" (pg. 28), what is otherwise called the ball-and-paddle genre (like in Video Games (Len Buckwalter, 1977, pg. 33)))

- Race Games (standard driving games like Night Driver, but also includes Dog Daze (1981), a game where two players (as dogs) race to be the first to "tag" fire hydrants that appear on the screen)

- Miscellaneous Games (games that Crawford couldn't decide how to characterize, including Donkey Kong, Frogger (or Preppie in the book's first printing), and Apple Panic (an unlicensed Apple II clone of the arcade game Space Panic))

Strategy

- Adventures (text adventure and graphic adventure games)

- D&D Games (CRPGs)

- War Games (like Computer Bismarck and Crawford's own best-selling Eastern Front 1941)

- Games of Chance (includes craps and blackjack. He states that these games "have not proven very popular" on computer and "show the folly of mindlessly transporting games from one medium to another" (pg. 37). I recall casino skill games like blackjack and poker being fairly ubiquitous during the 1980s. Perhaps their popularity was due to the string of strip poker titles published once home computer graphics reached a certain level of fidelity.)

- Educational and Children's Games (includes classic mainframe computer simulation games like Hammurabi and Lunar Lander, as well as Warren Robinett's pioneering Rocky's Boots, designed to teach kids about logic gates)

- Interpersonal Games (an undeveloped category at the time of writing, but one that would include Crawford's unpublished Gossip (1983) and later games like The Sims, Facade (2005), and probably the entire dating game genre)

No comments:

Post a Comment