I am happy to say that I was able to wrap up summer with some hands-on research at a terrific pinball parlor and video arcade while on an out-of-state road trip.

I always prefer to experience these works on original hardware and in their proper context, and this location did not disappoint. There was a lot of machines, including many that I've recently been writing about. Also, I got to play some rare finds like Hercules (1979), the largest production-model pinball table and Atari's swan song in the pinball industry.

This summer, I completed a digital project prototype and researched the evolution of game structures in the 1979-1982 period.

Taxonomy of Virtual Spaces Project

I completed a prototype of my project to explore different spatial paradigms seen in digital games (spatial paradigm defined as the visuo-spatial configuration of a virtual space and the player's affordances for navigating that space). My first test paradigm is the "Filmation" paradigm that became popular on the ZX Spectrum in the 1980s and is still used in games to this day (such as in Elephantasy: Flipside). My prototype approximates the environment and navigation of Knight Lore, probably the first game to use this spatial construction.

"Filmation" games use a pixel dimetric method of screen projection, common for "isometric" games of the era (such as Zaxxon and Q*bert). The prototype allows the player to press the "T" key to change projection method to true isometric (like Monument Valley) or pixel trimetric (like Crystal Castles). Some room arrangements become unclear or ambiguous with certain projection methods, making the spaces difficult for the player to comprehend or navigate. This may or may not be intended, as the level designer may use an ambiguous layout to trick the player with an illusion or create a difficult navigational puzzle to solve.

|

| In true isometric projection, my character appears to be in the corner of the room... |

|

| ...but it turns out that there is space between the top platform and the walls |

My development blog posts:

Initial plans and research

Refinement of terms

Preproduction

Production

Conclusions:

I have been able to replicate the "fake 3-D" environment from and older computer game and replicated it fully 3-D, polygonal game data. Reconstructing in this manner allows me to quickly test different projection systems (three options so far) without having to redraw or recalculate all of the art assets needed to display the space.

Next steps:

In the future, I need to expand my project to project other types of spatial constructions and navigation methods. My work on researching a "cartoony" spatial paradigm (see below) gives guidelines for what types of projections, "camera" angles, and types of environments would be best to start with.

The intent is to create a tool for testing and remixing different game qualities on the fly to see how these options change the player's phenomenological experiences of the same virtual spaces (say, playing a 2-D platformer game in first person). The point is not to replicate an entire game experience, but focus on the spatial qualities and navigation affordances. This type of tool is helpful in game development and other forms of research. This will also serve as a "museum piece" of various spatial paradigms in games, not dissimilar to Traversing Virtual Dimensions, my other project presenting the early development of digital avatar navigation.

Toward a "Cartoony" Spatial Paradigm

|

| Pac-Man (Namco, 1980) paragon of cartoony gaming |

Additionally, I performed some research on the 1979-1982 game era when what I call "cartoony" graphics developed and became popular both in the USA and Japan.

I see a lot of correlation between the visual techniques of early digital games and traditional cel animation, so I feel there is something to uncover at this point where games started to hew closer to cartoons (and I don't just mean Dragon's Lair). Both forms of media can use similar techniques to create a sense of space and enhance visuals.

|

| Parallax motion conveying deep space in Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro (1979) |

|

| Parallax motion conveying deep space in Moon Patrol (1982) |

Both examples above use scrolling graphics on layered planes to create hybrid, yet cohesive, images. In each case, the vehicle appears to move through deep space, yet the two vehicles never change their x positions in the respective images.

Many other techniques are common to both cel animation and game graphics: limited color palettes, simple shapes, repeated animation cycles, characters with big heads to show facial details, etc.

Conclusions:

My research uncovered that there is not one but several "cartoony" spatial paradigms that evolved from one another during this golden era of arcade games with character. These will be directly useful in expanding my own lexicon of paradigm variations and options to incorporate into my digital project.

This work is closer to the diachronic "art history" of evolving aesthetic styles I seek to create and I feel that my taxonomy of virtual spaces successfully conveys the exact spatial changes between game styles.

How did digital games get a "cartoony" look? Part of the reason is because of technological advancement was required before detailed player avatar graphics and animations (think sprites) could convey a sense of character. ROM chips allowed far more detailed graphics than earlier diode-based images. ROM chips started to be used in arcade games by 1974 but the first "cartoony" game Cutie Q wasn't made until 1979. Toru Iwatani was likely inspired by the immensely popular anime Obake no Q-Tarō that he watched as a kid when he made an aesthetic decision to incorporate big-eyed, round, ghost-like characters in the game (he admits it was his influence for Pac-Man). Note also the similar "Q" designs in the titles of both:

|

| Obake no Q-Tarō title card with upside-down smiling obake "Q" from the 1965 anime series |

|

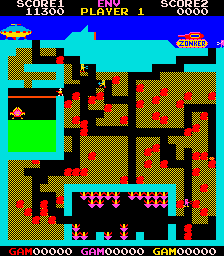

| Japanese Cutie Q arcade instructions with similar "smiling Q" logo at top |

It seems clear from my research that platformer games evolved from maze games. This is not surprising as "ladder" games have been considered a type of maze game. What is interesting is that Heiankyo Alien*, a little-known game here in the USA, may have been an influence on the biggest games of 1980 and 1981: Pac-Man and Donkey Kong (through influence on Space Panic).

*Fun fact: I bought my copy of Heiankyo Alien for Game Boy from fellow Drexel instructor and game history researcher Adrian Sandoval.

This section of study ends at 1982, which means there are plenty of other important examples that followed. 1983 would bring Bag Man, Bomberman, Congo Bongo, Crystal Castles, Mappy, Mario Bros., Tapper, Track & Field, and more. All this in the midst of an arcade market slump and an outright crash of the home game market in the USA. I plan to continue developing this series in the future.