Taxonomy of Virtual Spaces

In 2022, John Nesky (Feel Engineer on Journey (Thatgamecompany, 2012)) wrote a Twitter thread analyzing various stylistic choices a game artist may make when designing the boundaries of a 2-D game (like many 2-D platformer games). He preserved the thread as a Google document and in pdf format for easy reference.

|

| 2D Game Solid Boundary Types by John Nesky |

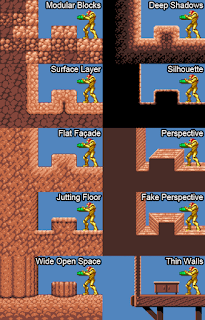

Nesky's analysis of visual styles has some crossover with my current work in analyzing the spatial paradigms of many platformer games. Each example image (see illustration above) features Samus Aran from Super Metroid (Nintendo, 1994) in an environment constructed by Nesky according to these different stylistic techniques. His design study tends to focus on 2-D platformers, but he also shows how the techniques work for other types of games.

2D Game Solid Boundary Types

Nesky defines 10 different art styles used convey the "fourth wall" through which the player views the game environment. The world is often presented as if in an architectural cross-sectional view, using the game's plane of action as the cutting plane. The navigable area of the game's environment is clearly rendered, but the internal structure of that environment (inside the walls, floors, and ceilings) may be abstracted (surface layer), hidden (silhouette), or stylistically presented (wide open spaces).- Modular Blocks

- Flat Façade

- Jutting Floor

- Surface Layer

- Deep Shadows

- Silhouette

- Perspective

- Fake Perspective

- Wide Open Spaces

- Thin Walls

Most of these styles are designed around the capabilities of tile-based environment graphics, like those seen in earlier game consoles like NES, SMS, SNES, and Genesis. These styles do not take foreground or background elements into consideration. They only focus on the environment along the game's plane of action.

Analyzing the Analysis

There are three types of projection methods here that line up with my Taxonomy of Virtual Spaces.

|

| Modular Blocks by John Nesky |

Orthographic (Modular Blocks, Flat Façade, Jutting Floor, Surface Layer, Deep Shadows, Silhouette, Wide Open Spaces, Thin Walls)

|

| Fake Perspective by John Nesky |

Oblique (various) (Fake Perspective)

|

| Perspective by John Nesky |

Perspectival (usually 1-point) (Perspective)

|

| Contrast the receding lines of Contra III and Link to the Past environments |

I responded to the question with the above altered screen shots and stated that one can trace the receding lines of the environment to see if they converge. Contra III's lines converge almost perfectly on the center of the screen. Each line is projected at a different angle. In contrast, Link to the Past uses a naive perspective technique with the receding lines of each corner of the environment projected obliquely at about 45° from the horizontal. This offers a convincing sense of depth and is fully in line with the art style of the original Legend of Zelda, but it is not a true 1-point perspective.

Odds and Ends

|

| The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past |

Nesky notes that Link to the Past uses different projection methods for indoor and outdoor environments. He refers to outdoor projection as orthographic, which I define as orthogonal (a classic "top down" view as opposed to a direct overhead view). He does note the unusual fact that you can see the horizon from the pyramid, something that should be impossible from a planometric projection! This is another example where the conceptual image plane of the background is rendered differently from the environment (see here and here).

|

| Horizontal oblique projection in Flashback |

Nesky also notes that Flashback's projection is "angled sideways," or in what is called a horizontal oblique projection. As he states, "This visually preserves precise vertical distances while adding depth to the world. Door frames and platform railings are rendered in front of the avatar." There are many doors in Flashback and this aspect is important to making them look like doors instead of walls.

Conclusion

Nesky is not an expert on the technical details of different projection methods, and he fully admits that is the case. But this was never the point of his study. His study focuses on the specific stylistic choices that game artists use (especially those making tile-based "pixel art" games) to define that invisible fourth wall that is coplanar to the player's screen. He has created another method of defining and grouping games by their aesthetic choices rather than purely by technical or genre classifications and I applaud his work.

No comments:

Post a Comment