|

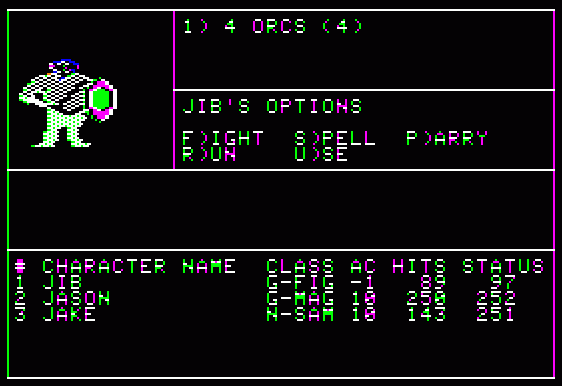

| Excerpt from the lecture Role-Playing Game History Part 4: Early Computer RPGs (Rowe (2024)) |

I subscribe to the theory that computer role-playing games (CRPGs) and adventure games (AVGs, an acronym that only caught on in Japan) tend to focus on specific aspects of the tabletop RPG experience. Each such aspect can be used as a frame of reference or lens through which a game may be examined.

The Tactical aspect of RPGs is exemplified by the movement of miniature figures representing player characters on a map during combat or exploration. This stems from D&D's origins with the medieval miniatures wargame Chainmail. The Storytelling or Conversational aspect is how tabletop roleplaying can be seen as friends sitting around a table and narrating a story together. The First-Person or Experiential aspect is seen in Live-Action Role-Playing (LARP), dressing up in armor and robes and attacking your friends with foam swords and tennis ball magic spells. LARPing the public's imagination in this early era with stories of illegal explorations of steam tunnels as ersatz dungeons.

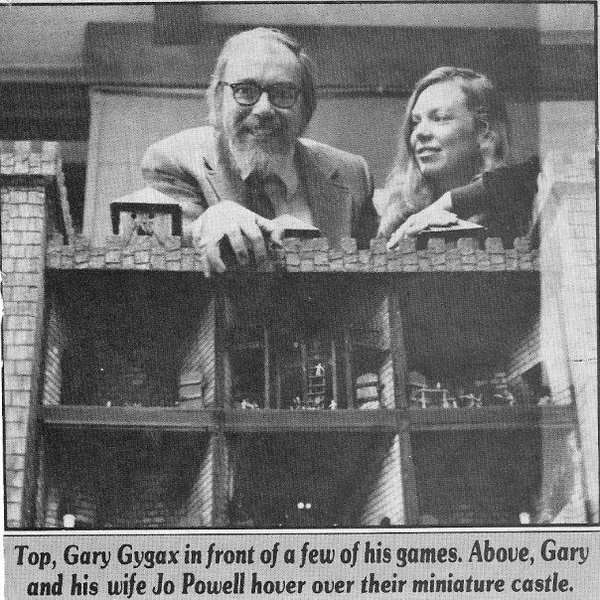

Illustrated graphic adventures convey the Dioramic aspect of set-piece environments made with miniature figures to create an artistic adventure scene. Such scenes are closely related to the RPG hobby, populated with painted game figures. They were typically used as store displays to generate interest in the games, not to fight out in-game tactical situations.

|

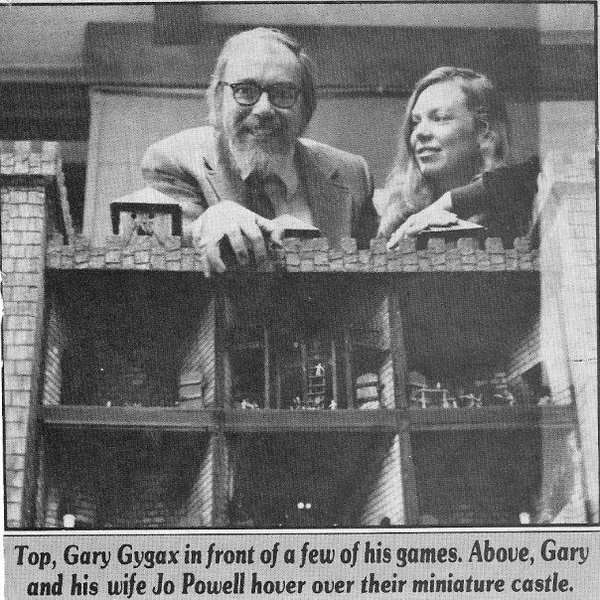

| Gary Gygax and Mary Jo Powell (Gygax) with Sutherland's castle diorama (source unknown) |

|

| Mary Hendryx with Sutherland's castle diorama (Kevin Hendryx (1981)) |

A perfect example of this such a diorama is the three-story castle created by David C. Sutherland III and displayed in TSR's Dungeon Hobby Shop in Lake Geneva, WI (see above). The castle was divided into nine rooms organized both spatially and temporally. The sequence of room follows the story of a party of adventurers as they fought their way through the structure. Only a handful of the adventurers survive long enough to battle the demon lord in the last room. This was a piece of art to be viewed and enjoyed, not an environment used during gameplay.Tactical (RPGs)

|

| A "family tree" of early CRPG influences from Role Playing GameSide (2014) vol. 1 (image source) |

Rutherford's work inspired many other PLATO CRPGs, such as dnd, Oubliette, and Moria. Telengard, in turn, was influenced by (or heavily "adapted" from) dnd, making a break onto personal computers when it was published by Avalon Hill.

|

| Party of D&D adventurers facing a gelatinous cube (photo by author) |

Many CRPGs used the spatial techniques of pedit5, where environments are rendered in plan orthographic view, much like the maps of tabletop D&D dungeons. Characters are shown in elevation view, typically standing and front-facing to better show recognizable details in a small image. This hybrid combination (bird's eye view of the map, front view of the characters) is a simple method to replicate miniature figures positioned on a tabletop map with 2-D graphics. Miniatures are not required to play tabletop D&D, but many players use them to keep track of combatants' tactical positions during battles or the party's position on a wilderness map during overland travel.

|

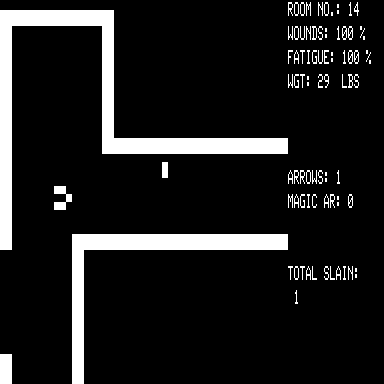

| Dunjonquest: Temple of Apshai for TRS-80 (Jim Connelly, Jon Freeman and Jeff Johnson (1979) Automated Simulations Inc.) |

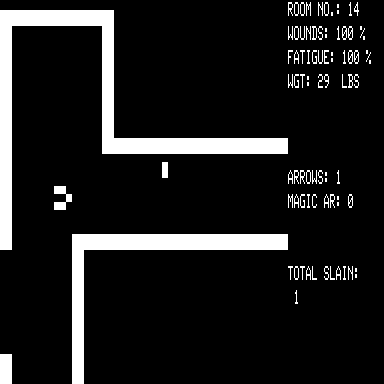

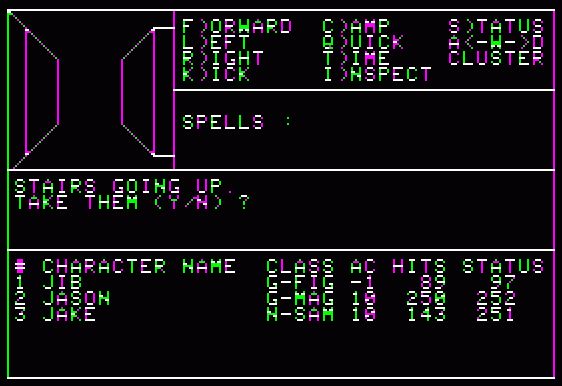

Temple of Apshai was an early CRPG first published for the Commodore PET and TRS-80, two personal computers that were so limited, they weren't capable of bitmapped graphics (see above) and the rulebook had to be referenced for detailed room descriptions. The creators were experienced D&D players who set out to capture the tabletop experience on computer. Dungeons are navigated in a similar manner to pedit5 with sections of the map revealed as the player character moves. Notably, this game does not use a grid map per se and the player character could travel a variable distance with each move.

|

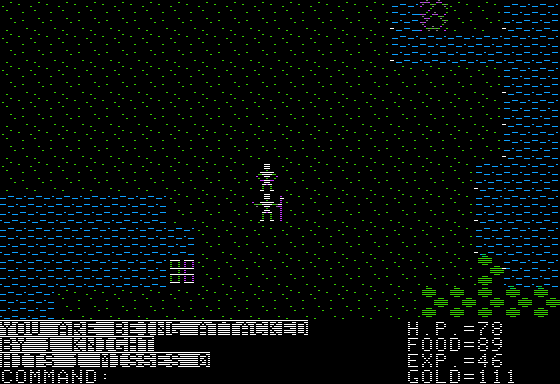

| Ultima (Richard "Lord British" Garriott (1981) California Pacific Computer) |

Richard Garriott learned how to play D&D, learned computer programming, and gained the nickname "Lord British" all while attending a computer summer camp. When he returned to high school, he started developing a series of CRPGs in BASIC on his school's teletype terminal connected to a PDP-11. These early games used text characters as tiles to show the player's dungeon environment, printing out a new map with every move. His early games (titled DND1 to DND28B) evolved into his first published CRPG, Akalabeth for Apple II. Akalabeth included an overhead world for the hero to navigate, dotted with dungeons that the player explored in first-person views (see below for more on Akalabeth's dungeon views).

Akalabeth was followed by the first Ultima game with the explorable world of Sosaria, complete with oceans, land masses, and different terrain types. As Card describes it, "The Ultima series... uses an overhead camera most of the time, looking down on events the way you look down on a map" (Compute! #97). Sosaria expands far beyond the extents of a single computer screen and is divided in a square grid, much like the graph paper used to draw maps for tabletop adventures. This also made movement simple, like moving a piece orthogonally on a chessboard. When the player lands on a town tile, the view is "zoomed in" to the contents of that tile and the world view is replaced by a map of the town buildings, shops selling food, weapons, armor, etc.

Ultima III: Exodus and Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar employ the same spatial paradigm for overland (and oversea) travel. In those games, the player controls a party of adventurers instead of a lone hero. When monsters are encountered in the wilderness, the scene "zooms in" to a battle map with a different grid scale, where each party member can be tactically positioned. These games also trace the player party's line of sight, so that occluded sections of a map are not rendered. As Card described, "A picture of one man represents your entire party... However, the map only shows you what your character can actually see. Anything around the corner of a building or deep within a forest shows up as black on your screen and becomes visible only when you put your character in a position to see it" (Compute! #97). "Each place is the size of a single letter on a normal text screen. The characters are tiny, but they can be in thousands of places in the course of a game" (Compute! #98).

Card considers the tradeoffs between graphic fidelity loss with tiled objects and the benefit of a massive virtual world to explore. "The map approach makes sense... In play, you can always see what's going on and the screen is alive with images. To program it, the designers only had to store the graphic image of a whole bunch of tiny reusable objects. But this approach, successful as it is, remains schematic, not movielike" (Compute! #97).

|

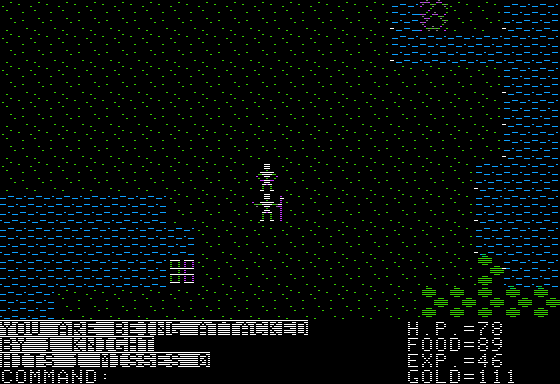

| Rogue for UNIX (Glenn Wichman, Michael Toy, and Ken Arnold (1980)) |

Glenn Wichman and Michael Toy were two students at UC Santa Cruz who played D&D and were learning computer programming. Both were inspired by Colossal Cave Adventure (see below) to create new text adventures to challenge each other. Eventually, they hit upon the idea of creating a graphic version of a text adventure, something that would surprise even the designer with something new in each playthrough. With help from Ken Arnold, they were able to use text characters for the graphics and wrote procedural generation routines to randomize dungeon maps, magic item effects, monster placement, and treasure. From this, Rogue was born. The game functions on the same 80-column grid used natively for text display, with each character space serving the same function as an Ultima grid tile. The virtual game world is restricted to just the dungeon, with no overworld to explore. With its smaller scale, Rogue is more similar to earlier titles like pedit5 and dnd, although the creators probably never saw a PLATO system.Conversational (Text Adventure Games)

|

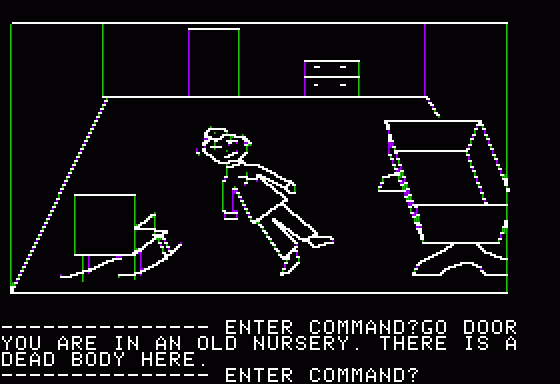

| Early version of Colossal Cave Adventure (Will Crowther (1976)) |

William Crowther was a programmer at Bolt, Beranek and Newman (BBN), helping lay the foundation for the nascent ARPANET. He was also an avid caver and rock climber and loved to explore the outdoors. His friends introduced him to the then-new game of D&D around 1975 and Crowther rolled up his character, "Willie the Thief." In 1976, he decided to write a computer game in FORTRAN that he could share with his daughters, a project that combined all three of his passions (programming, caving, and D&D). The PDP-10 he developed on didn't have much capacity for graphics, so all of the game information is conveyed by text. He also struck upon the idea of controlling the game through the use of a text parser - the player would type commands with natural English words and the program would interpret them and translate them into game actions. He finished Colossal Cave Adventure (often just called Adventure) and shared the game on the ARPANET, where Don Woods discovered the game and expanded it (with Crowther's permission). This updated version spread like wildfire, inspiring countless other programmers to create their own additions to this new text adventure game genre (a.k.a. interactive fiction).

Crowther's text parser puts the player in a sort of conversation with the computer program, mirroring the interaction between DM and player in a game of D&D. The DM describes the player character's surroundings and often asks, "what do you do?" The player responds by describing their character's actions. The DM determines the results of the actions and informs the player what happens next. This is exactly the same feedback loop seen in text adventures.

Many earlier mainframe games used text description (notably Hammurabi and The Oregon Trail), but those games did not use Adventure's conversational approach to gameplay.

Text adventure games are typically presented in a second-person point of view (in contrast to graphical first person and third person games). The program often addresses the player character as "you" and describes where "you" are ("YOU ARE STANDING AT THE END OF A ROAD..."). This is a literary game genre (or literate, anyway) with virtual spaces navigated through hypertext. Text adventures transform a database of objects and locations into a navigable virtual world, vividly described and rendered in the graphics of the imagination.

|

| Zork (with the working title of Dungeon) (Lebling, Blank, Anderson, and Daniels (1977)) |

It is hard to overstate Adventure's affect on the nascent computer game industry. The game inspired students at MIT to create their own massive mainframe adventure: Zork. The team formed a new company, Infocom, to publish Zork and many other text adventures for personal computers. Scott Adams played Adventure at his job at an electronics manufacturer, which inspired him to write his own AVGs for the TRS-80 and other personal computers. Roberta Williams was hooked after she first played Adventure, causing her to track down every other text adventure she could find. Roberta added graphics to the adventure game formula, creating Mystery House, the first graphic adventure game. Arguably, the early graphic adventures went on to inform the entire genre of visual novels in Japan. Roy Trubshaw at the University of Essex played an early build of the mainframe version of Zork (called Dungeon at the time), which inspired him to team up with Richard Bartle to create a multiplayer version of the game: M.U.D. (short for Multi User Dungeon). M.U.D. spawned an new genre of MUDs, which directly inspired the creation of graphic MUDs, soon referred to as MMORPGs (Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games). First-Person Experiential (RPGs)

|

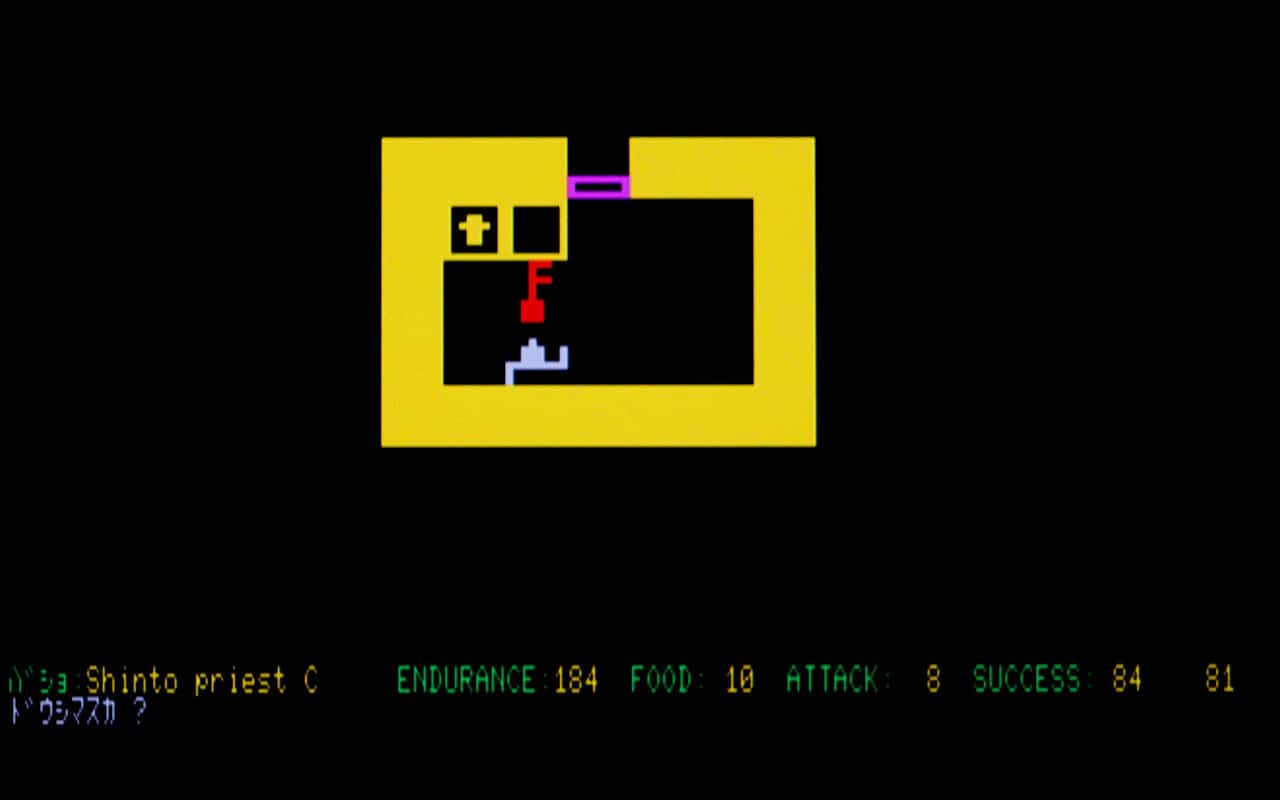

| A tiny dungeon view in Moria (Kevet Duncombe and Jim Battin (~1978?)) (image source) |

|

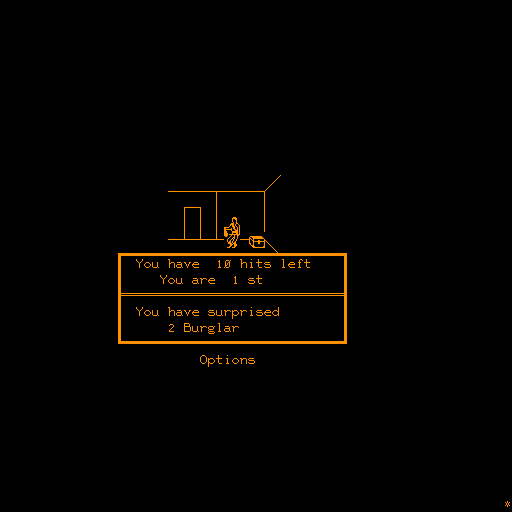

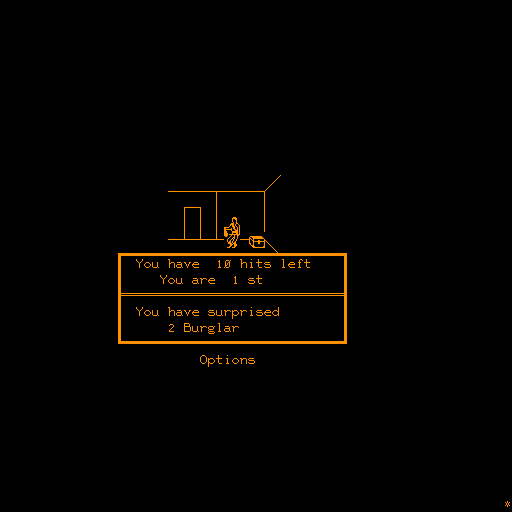

| Catching burglars by surprise in Oubliette (Jim Schwaiger (~1977-78?)) |

|

| Maze War running on an early 1970s Imlac PDS-1, as featured in a 2004 DigiBarn Computer Museum restoration project. (image source) |

|

Moria and Oubliette's 3-D wireframe tunnels in one-point perspective closely mirror the rendering techniques seen in earlier computer games like Maze a.k.a. Maze War (Colley, Thompson, and Palmer (1973) and Lebling (1974)).

|

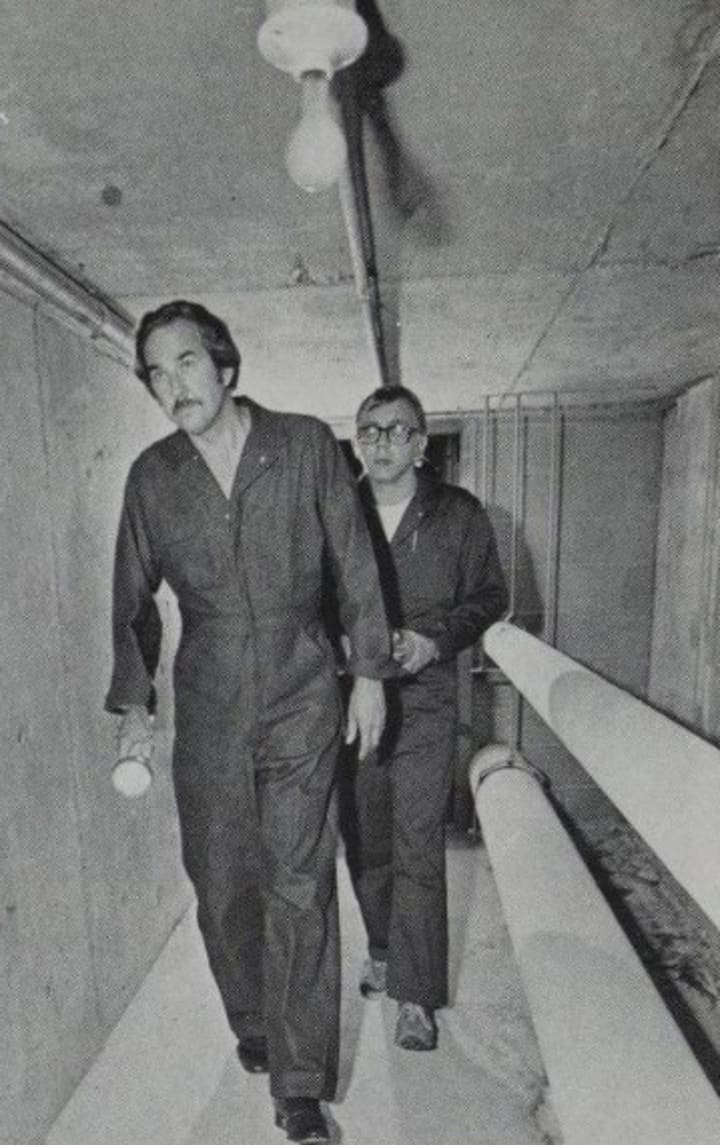

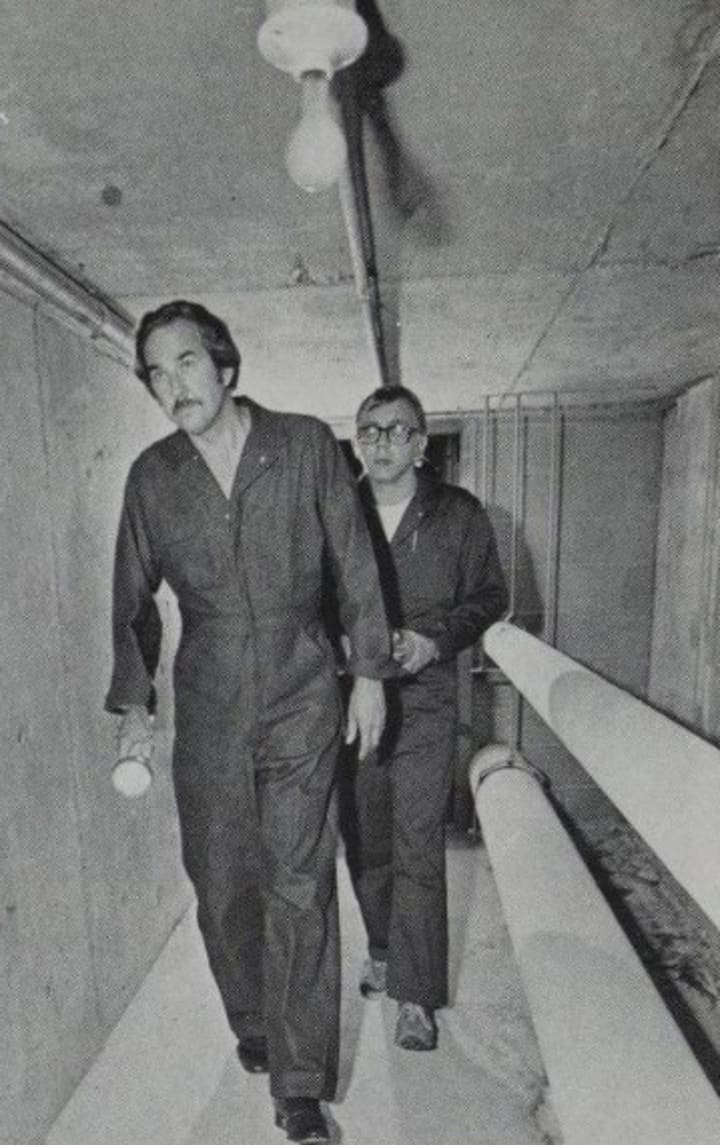

| "William Dear and his colleague Dick Riddle walk through one of the cleaner and more accessible parts of the tunnel" (Pat Beck (1979) Detroit Free Press) reprinted in The Dungeon Master (William Dear (1984)) |

First person dungeon crawl games rose to prominence on personal computers in an era when the public vision of D&D often involved getting lost in underground steam tunnels. A young computer science student and D&D player named James Dallas Egbert III disappeared from his dorm room at Michigan State University in 1979. Investigator William Dear hypothesized that Egbert was lost in the eight miles of steam tunnels that run underneath the MSU campus while playing a live action D&D adventure. Egbert was not in the tunnels, but the image that playing D&D literally involved creeping around underground in low-ceilinged, rectangular tunnels (see above). The 1981 novel Mazes and Monsters iserved as a fictionalized retelling of Egbert's tragedy, and was made into a TV movie of the same name that year (with Tom Hanks in his first leading role). Mazes and Monsters propelled the steam tunnel myth over the TV airwaves as the Satanic Panic was starting to grip the USA.

|

| Richard Garriott in character (Richard Garriott (ca. 1981)) (image source) |

The experiential nature of living a fantasy adventure through one's own eyes is also close to LARPing and similar forms of role play, like the Society for Creative Anachronism (SCA). Richard Garriott was a member of the SCA (see above), like many luminaries of tabletop RPG design, like Steve Perrin (RuneQuest, Stormbringer), Steve Jackson (The Fantasy Trip, GURPS), and Aaron Allston (Autoduel Champions, Justice, Inc., Dungeons & Dragons Rules Cyclopedia). SCA members create medieval personas, dress in period garb, and participate in medieval era activities (tournaments, crafting, banquets, brewing, heraldry, etc.). It is not a Live Action Role Playing game, but shares some of the same aspects (including swordfights and similar mock battles). This might be seen as the ultimate expression of first person play.

|

| Akalabeth (Richard "Lord British" Garriott (1980) California Pacific Computer) |

The Ultima series is typically associated with its tile grid overworld map, but Garriott's games also feature underground exploration using a 3-D first person view. As Card described the Ultima series (and Akalabeth), "only in the corridors of the dungeons do you find yourself looking at the scene from eye level" (Compute! #97). Monsters can be spotted in the distance and will be seen advancing into melee range, one grid unit at a time, something missing from Wizardry. |

| Dungeon Master (1987, FTL Games) |

Dungeon Master took advantage of the advanced graphic capabilities of the new 16-bit computers that were available in the late 1980s. This game evolved the Wizardry paradigm by adding real-time play and new ways to interact with the first person view (objects can be manipulated in the scene with the mouse cursor, groups of enemies can be seen moving at a distance, doors animate open and closed).

Dioramic (Graphic Adventure Games)

|

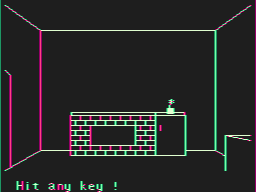

| Mystery House (Roberta Williams (1982) On-Line Systems) |

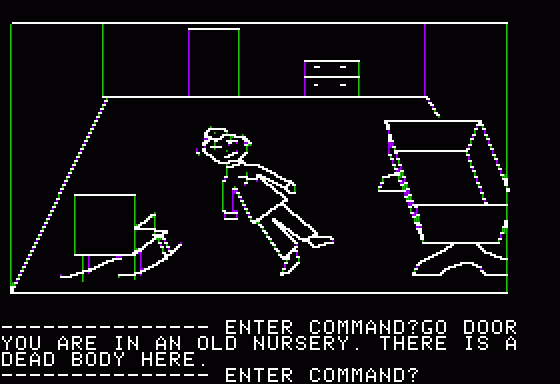

Ken and Roberta Williams are credited with adding images of scenes described in text adventure games and creating the new genre of graphic adventure games. Early graphic adventures used a hybrid approach, where the screen is dominated by an image with a small region for text underneath it.

The Williams' early graphic adventures (the Hi-Res Adventure series) showed fairly static drawings of the scenes that are described in text. The player still interacts with the text parser in a conversational method, typing short commands for their character's actions. As the player's actions make changes in the scene (pick up item, open door), the graphics are changed to show the updated state of the game.

|

The Dark Crystal (Roberta Williams (1983) Sierra On-Line)

|

The graphics in these games often show environments in one-point perspective with an elevated point of view, much like looking into a miniature diorama from above. Note that Hi-Res Adventuer #6: The Dark Crystal is an unusual adventure game title as the story is told in third person instead of second person point of view (the game refers to the player character as "Jen" instead of "you"). Another unusual aspect is that the player character is seen in the game's environment. With other graphic adventures, it is often assumed that you see the world as if through your own eyes.

|

| "Terraced Room" (David C. Sutherland III (1979) S2: White Plume Mountain, TSR) |

These early graphic adventure examples remind me of illustration booklets included in some of TSR's AD&D adventure modules (notably in the "S" series of modules). As the player characters enter a new area, the dungeon master would show the players a keyed illustration of the environment. This was especially helpful for complex spaces that are difficult to describe (such as the complex "Terraced Room" full of monsters, above).

|

| King's Quest (Roberta Williams (1984) Sierra On-Line) |

After a few years, the Williams evolved the graphic adventure concept with the King's Quest series. The game screen is still a mix of graphics and text, but the graphic image had become a navigable space to explore, not just a static view. The player's character Sir Grahame is represented on-screen with a colorful sprite that can be controlled on the screen with a joystick (a big change from the static views of Jen in the world of The Dark Crystal). The player can use a combination of joystick to move and typed commands for other actions. Players at the time were mostly impressed with this new paradigm, with numerous reviewers declaring "it's like playing an animated cartoon."

The King's Quest style of games used a similar dioramic view as earlier graphic adventures, with each scene typically drawn in one-point perspective. The interior spaces look like little shoebox dioramas, with one side and the lid removed from the box. The player character navigates to other spaces by moving to the edge of the screen or crossing a threshold (like a door). The new environment image is drawn to the screen with the player character moved as if entering the new space from the opposite screen edge.

Card reviewed Sierra's The Black Cauldron (1986), based on the Disney animated film of the same name. The Black Cauldron looks and plays like King's Quest and even uses the same Adventure Game Interpreter 1 (AGI1) engine. Card stated that this game "feels like an animated movie. Instead of the overhead map shots of Ultima... or the point-of-view shots of Bard's Tale... The Black Cauldron shows the main character... moving through a remarkably detailed scene - just like a movie" (Compute! #98).

Card and his children were impressed by seeing the player character (Taran) moving through the environment, taking actions, and interacting with other characters. What they describe is like watching a puppet or actor on a stage under the player's control. "We could move Taran behind trees, rocks, or buildings, and he'd disappear... When we moved him into the stream, he swam. When we used a magic spell, he flew... Other characters moved around him; the goat butted him, and he fell down. The whole family gathered around to watch as each child explored the world of The Black Cauldron" (Compute! #98). Card's review may have been, shall we say, overzealous when he declared that, "Sierra has done for home computer animation what Disney did for the cartoon back in the 1930s" (Compute! #98).

Evolution in Japan

These spatial paradigms for CRPGs developed in the USA soon made their way to Japan, where game designers adapted these graphics methods in innovative ways.

|

Text commands in Dragon & Princess (Koei (1982))

|

|

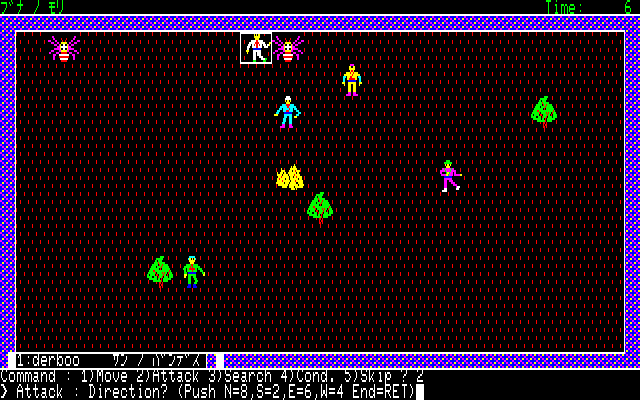

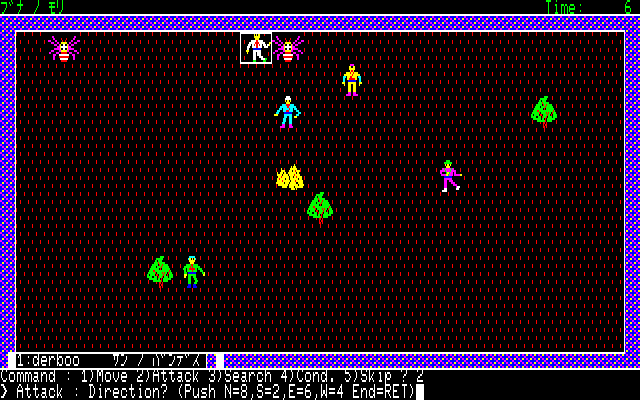

| Tactical combat in Dragon & Princess (Koei (1982)) |

Koei's Dragon & Princess is an unusual title. Most of the game is played as a text adventure, but battles are waged on a tactical map, predating Ultima III's tactical combat screen by two years (see above).

|

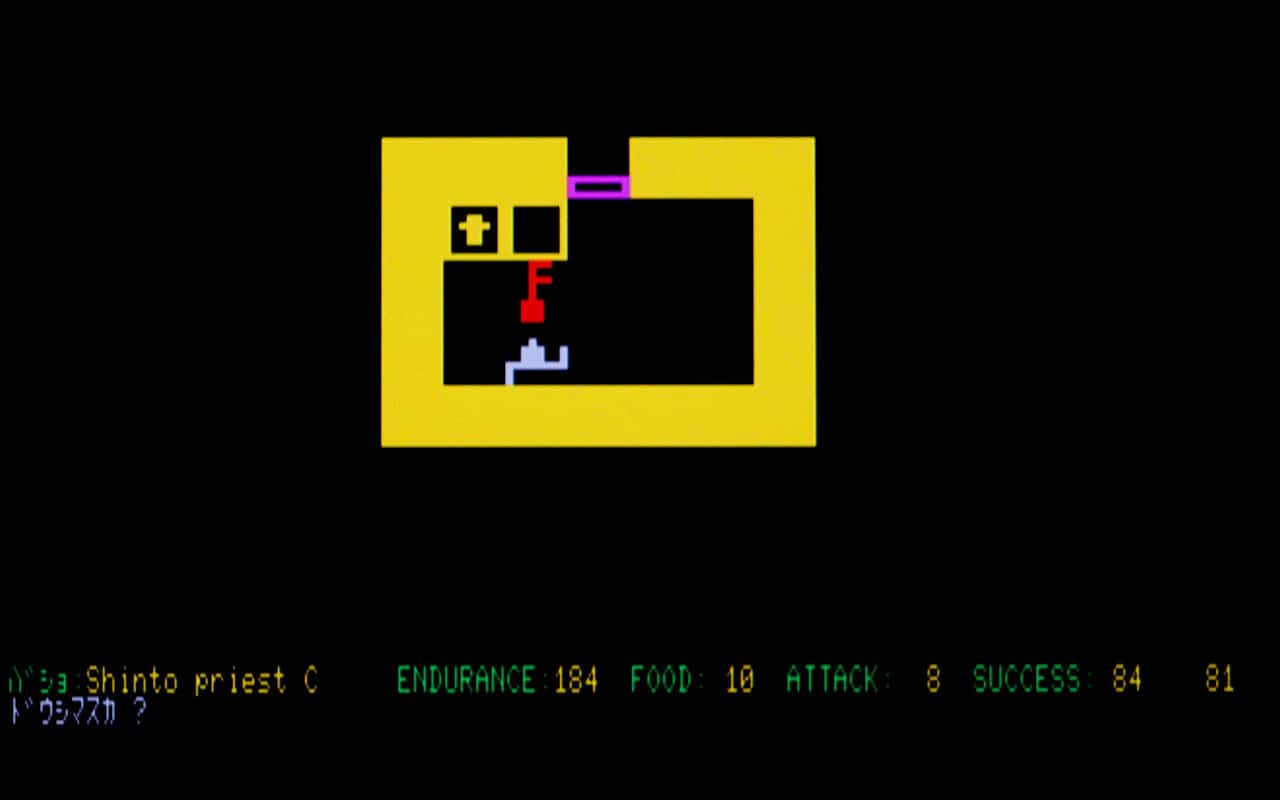

| クフ王の秘密 The Secret of Khufu (Koei (1983)) |

The Secret of Khufu is a dungeon crawler set in an Ancient Egyptian pyramid and bills itself as a "ROLL PLAYING GAME." It uses a plan orthographic view (birds eye view) for the environment, much like the Ultima series. The player character is also rendered in the same method, a strange gray figure with arms flailing in two directions and a prominent nose facing forward. This loses much of the recognizable details of Ultima's elevation view front-facing characters. The blocky graphics are similar to those seen in early versions of Temple of Apshai.

|

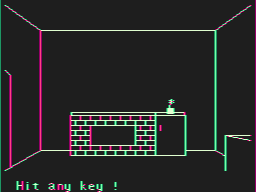

| ミステリーハウス Mystery House (Toshihiro Shintai (1982) Micro Cabin Corp.) |

Mystery House is sometimes called the first Japanese graphic adventure game. It appears to be inspired by Roberta Williams' game of the same name and features similar dioramic line drawings of the house interior. Unlike the original Mystery House, this game is a treasure hunt instead of a murder mystery.

|

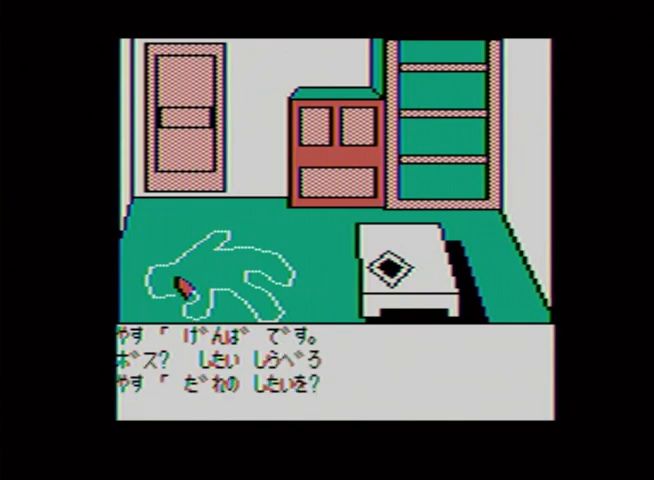

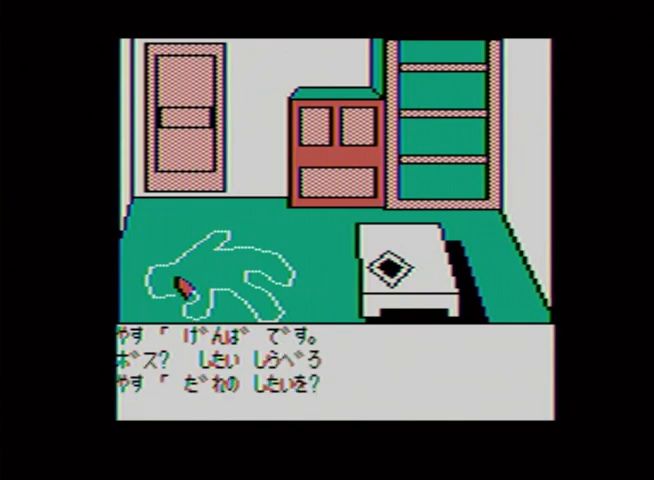

| ポートピア連続殺人事件 Portopia Serial Murder Case for PC-6001 (Yuji Horii (1983) Enix) |

The graphic adventure Portopia Serial Murder Case was one of Yuji Horii's first published computer games. As can be guessed from the title, this game is a murder mystery, with the player in the role of a police detective who must solve the crime by exploring the city of Kobe. Horii specifically wanted to write a program in which the player is having a conversation with the computer.

|

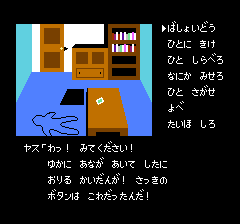

| ポートピア連続殺人事件 Portopia Serial Murder Case for Famicom/NES (Yuji Horii (1985) Enix) |

|

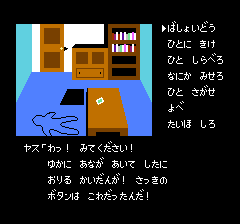

By 1985, Horii was partnered with Koichi Nakamura to port Portopia to Nintendo's Famicom console (NES). Hori and Nakamura had travelled to an Apple festival in California together where they first laid eyes on Wizardry, which they were clearly inspired by. The Famicom version of Portopia is different from the original versions of the game for computers. For one thing, there is a secret door in the floor near where the body was found.

|

| ポートピア連続殺人事件 Portopia Serial Murder Case for Famicom/NES (Yuji Horii (1985) Enix) |

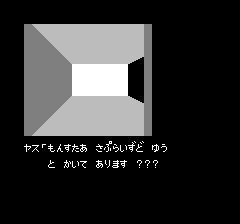

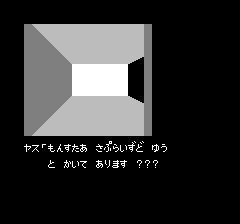

The secret door leads to a vast underground basement labyrinth, explored in first person view and looking very similar to a Wizardry dungeon (it even has some one-way walls). This is a somewhat jarring sequence which is completely unlike the standard graphic adventure presentation of the rest of the game. Nevertheless, this version of the game, with its "mystery, a 3D dungeon, and humor" is a major reason why Hideo Kojima decided to start making games. If there is any doubt that this labyrinth is inspired by Wizardry, your police assistant Yasu reads some graffiti on the wall that proves it (see above).

ヤス「もんすたあさぷらいずどゆうとかいてあります???」

Yasu: "It says 'MONSTER SURPRISED YOU'???"

|

| Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord (Andrew Greenberg and Robert Woodhead (1981) Sir-Tech) |

Wizardry pops up a "THE MONSTER(S) SURPRISED YOU" message when your adventuring party is ambushed by monsters in combat. It was a message that some Japanese players found puzzling.

|

| ドラゴンクエストへの道 Road to Dragon Quest manga (Enix (1990)) |

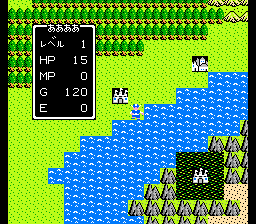

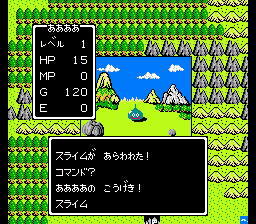

Horii and Nakamura were heavily inspired by both Wizardry and Ultima (see above) when they set out to create an RPG for the Famicom/NES console. Their goal was to combine the large overworld of Ultima with the character graphics and leveling of Wizardry, but the entirety of the game had to fit into two 32KB ROM chips for Famicom. Horii reached out to artist Akira Toriyama (Dr. Slump, Dragon Ball) to design the art for the game, and thus the main Dragon Quest (a.k.a. Dragon Warrior in the USA) team was assembled.

|

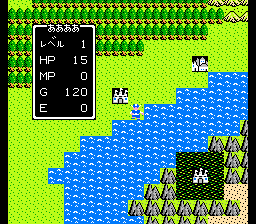

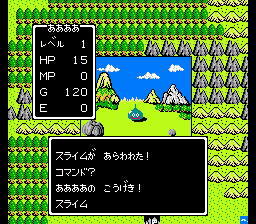

| Tiled overland travel a la Ultima, Dragon Quest (Horii, Nakamura, and Toriyama (1987) Enix) |

|

Full length combat portrait a la Wizardry, Dragon Quest (Horii, Nakamura, and Toriyama (1987) Enix)

|

Dragon Quest was a huge success in Japan and set the prototype for what would later be called a JRPG, typically defined as a digital RPG designed in Japan with game console friendly controls, manga-inspired graphics, and an epic storyline. The game was kept simple to adapt to game console play, with the player controlling only a single character. Akira Toriyama filled the game with charming and memorable creatures. As for the story, the evil Dragonlord has plunged the land into chaos and you, the hero, are the only one who can defeat him. For a touch of personalization, the player can choose the name of the hero and text boxes will refer to them by name.

Final Note: Lebling is Everywhere

While writing these notes, I noticed that one name kept popping up again and again: Dave Lebling. Lebling was at MIT's computer science lab in 1974 when he helped make an 8-player version of Greg Thompson's Maze/Maze War, probably the first networked first person shooter. Soon after Will Crowther stopped playing in the "Mirkwood Tales" D&D campaign with his buddies at BBN, Lebling joined the group. There was also his Imlac ports of Spacewar!, Hunt the Wumpus, and his trivia game created with thousands of questions sourced from the ARPANET.

All that was before Lebling co-authored Zork with other folks at MIT and helped found Infocom, the biggest name in text adventure games throughout the 1980s.

No comments:

Post a Comment